Fiber with Guts: Soft Flesh and Volatile Insides

Published January 16, 2025 in BmoreArt

From a monumental spiderweb constructed with leggings, to plush guns that rattle, buzz, and shake, to tufted rugs and custom pillows, Soft Flesh and Volatile Insides upends expectations in Goucher College’s Silber Gallery. This group exhibition—including works by Monique Crabb, Charlotte Richardson-Deppe, Ash Garner, and Stephanie J. Williams—utilizes textile as a core material and its softness becomes a vehicle for tension, unease, and critique. Across the show, textiles are not employed decoratively or nostalgically, but instead operate as a means of probing the body and broader systems of labor, violence, and precarity.

Monique Crabb’s works are displayed near the entrance of the gallery. Using tufted fabric and mixed-media, Crabb calmly, with “Bad Mother,” and explosively, with “Don’t Worry I’ll Clean It Up,” presents two fairly contrasting approaches to what she describes as “forms that reflect both personal and collective histories.”

Monique Crabb

Monique Crabb

“Bad Mother” is a nearly 6ft by 4ft tufted red rectangle with the title text spelled out in soft pink. In three lines of text, with three characters in each line, the work disjoints a phrase that in another context would likely feel biting and harsh. While the piece feels like it could be a soft and simple decorative object, it cues the viewer into a much deeper inquiry by the artist. This work speaks to a contrastingly sharper, perhaps more painful, sense of self doubt or maybe as an externalized reaction to unjust criticism.

Similarly, “Don’t Worry I’ll Clean It Up” references exhausting tasks through a black and white checkered installation which features the title text covered in and surrounded by pink liquid and ceramic Pepto-Bismol bottles. The use of Pepto-Bismol itself references care whether for self or others but the combination of the text and the chaotic pink splattering on the floor and wall suggests a haywire household. These two works, critical of societal expectations and constraints of women, are not only engaging formally and compositionally but also effectively unsettle preconceived notions of so-called “craft” materials (textile and ceramics) as well as non-”precious” media (sculpted paper pulp.)

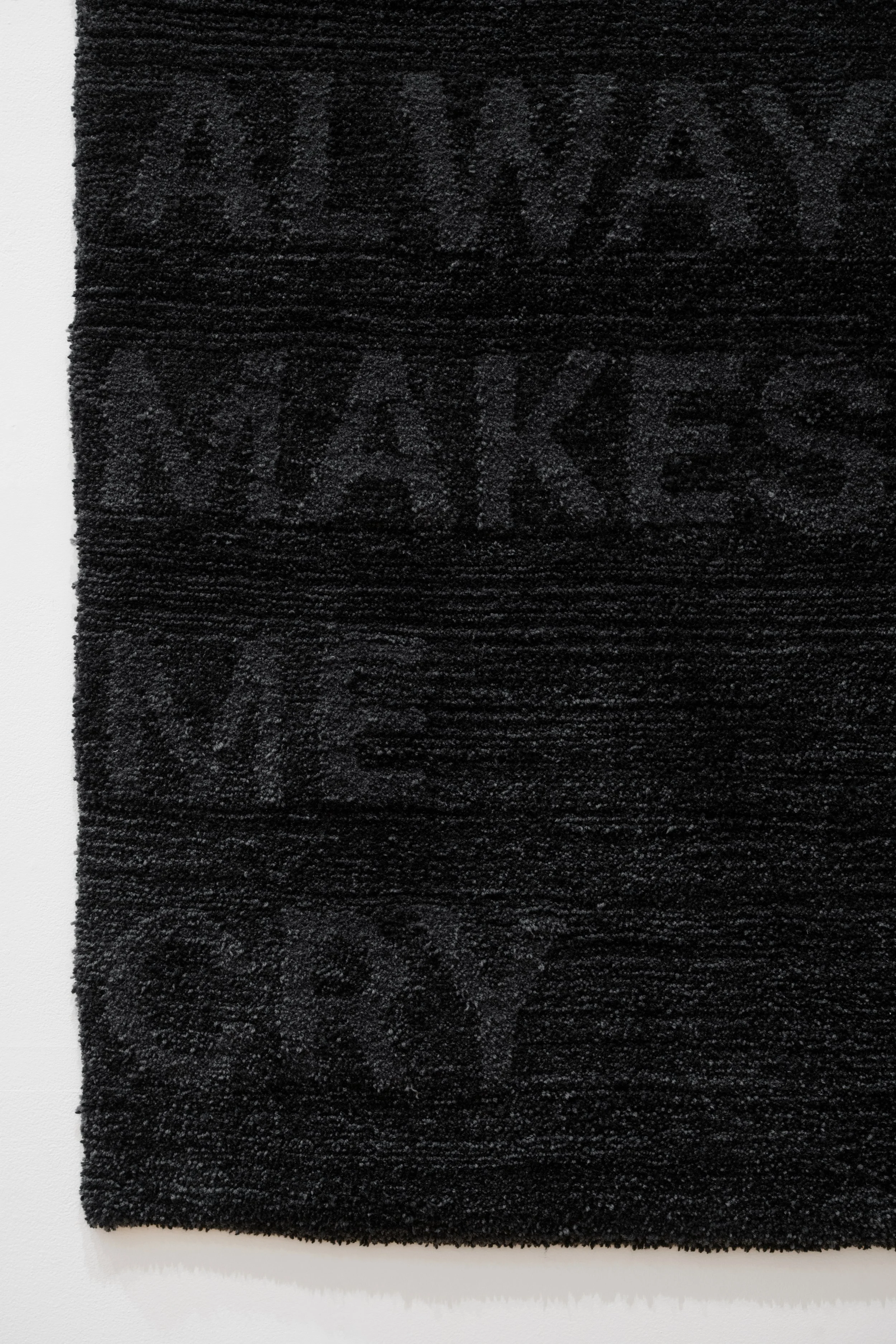

Crabb’s gray-on-black tufted diptych, “I Close My Eyes to See,” reads “ALWAYS THE DREAMER NEVER THE BELIEVER” and “DREAMING ALWAYS MAKES ME CRY.” Like in “Bad Mother,” Crabb utilizes the same all-caps, sans serif lettering style, though here the text is aligned to the left of the composition as opposed to being centered and filling the entirety of the space. These works are also markedly more subtle than “Bad Mother,” particularly for their lack of color. While the red and pink color scheme in Crabb’s work from the front room does not contrast in an abrasive way, her use of grey on black in “I Close My Eyes to See” is almost so subtle that it is difficult to digest from too far away. The viewer has to come close to these works to read their lyrical phrases and, as with most good poetry, walks away pondering its meaning and how those syllables may relate to their own lives.

Charlotte Richardson-Deppe (L) and Stephanie J. Williams (R)

Moving from the Silber gallery’s smaller front room to the lofty interior of the main gallery space, you will quickly be struck by the massive works of Charlotte Richardson-Deppe and Stephanie J. Williams which effectively activate the space.

The hanging works of Stephanie J. Williams are perhaps the most resonant with the show’s title. “No Name Kidney” hangs near eye level and in scale to an average human torso, two more of her works, “As Much You As Me” and “Expectation,” are hung much higher and from top to bottom are nearly 15 feet in height. These pieces go well beyond the scale of a human body but still maintain a complicated interconnectedness that feels like they could be taken from medical diagrams. Entrails, organs, veins and orifices all seem recognizable but illegible in a traditional biomedical sense.

Williams’ use of fabric transforms the pieces into something much more than the sum of their parts. Thin blue threads create meandering, varicose veins in “No Name Kidney.” Sacs filled with sand pull, anchor, and give visual and literal weight to the hanging viscera in “As Much You As Me” and “Expectation.” And perhaps most striking, fabric twisted and folded in on itself creates orifices on each of Williams hanging pieces.

In their artist statement, Williams talks about wanting to grow up to be a butcher and how the resulting parts and pieces of that process can be changed when turned into a meal. Though I see the work in Soft Flesh, Volatile Insides as much more of a post-mortem dissection than a butchering, she certainly takes these abstracted, anthropomorphic forms and transforms them in a way that is not only visually striking but beautifully engages the space in which they are shown.

Stephanie J. Williams

Stephanie J. Williams (detail)

Williams also has one piece, “Missing the Good Stuff,” that lies heavily on the ground and is connected by a dozen or so feet of fabric to the wall farthest from the entrance to the gallery. This work is a busy and colorful pile of mostly intestinal forms with thin snake-like appendages that almost appear to be feeding on it. Some of the plaid, lamprey-like creatures are on their way towards the piece’s nucleus while others have already latched on. These linear elements are found on the opposing side of the piece to a long stretch of fabric which acts as a failing lifeline, a final connection to a body unable to fend off parasitic invaders.

The work feels direly vulnerable, left on the ground where it doesn’t belong; it is being attacked and damaged. While the busiest and central mass of the composition are modestly sized in comparison, the addition of these two linear elements stretch and expand the work to nearly a quarter of the gallery’s length. The sense of movement and scale leads into the massive net that Charlotte Richardson-Deppe has created nearby.

Charlotte Richardson-Deppe has two very distinct works in this show; “Net,” is the hardest to miss. It is a massive spider-web like form created from black leggings that have been sewn together and hung across one of the gallery’s corners. The leggings aren’t immediately discernable from a distance, it is only once you come up close to the work that the material becomes eerily recognizable. This renders it inherently referential to legs but what I find beautiful about this piece is that the shapes start to look like more: arms, torsos, even full human bodies. Once you’re up close and personal, “Net” oscillates between a benign, soft web form, and sinister constructions of bodies sewn together.

Richardson-Deppe’s other works contrast quite a bit from “Net” but similarly subvert the benign to display something more sinister upon further inspection. “Death Rattles” are soft, fuzzy, stuffed forms that resemble guns. Some of the rattles have the unmistakable high pitched tone of a dog’s “squeaking toy” while others have pull strings that cause them to shake and buzz. Meant to be engaged with, the works are unnervingly cute, fun, and playful given the subject matter that they and their title allude to.

Death rattle, “a rattling or gurgling sound produced by…a dying person” functions as an effective play on words. Not only does it reference the key component of sound in these pieces but it effectively juxtaposes the somber seriousness of “death” with the childlike amusement of a “rattle” Richardson-Deppe says of the work: “In our devastating and violent political landscape, I grasp at absurdity. I have made ineffectual weapons from untethered limbs, distilling levity and violence into a squeaky and squishy form.”

Ash Garner

Ash Garner’s installation, “The Very Hungry Millennial,” leans much more into the volatility referenced in the show title, making comment on the precarious and unpredictable lives of college educated millennials. The piece, named after the book The Very Hungry Caterpillar written in 1969 by Eric Carle, features a number of tropes and icons often employed by and about millennials to express formative qualities. The aforementioned caterpillar is central to the composition, clear and flattened in areas with “X”s for eyes and a chip reader credit card for a mouth. In the background, “Billing Issue” is written in cursive with LED lights. It is surrounded, almost in nimbus-like fashion, by a yellow pill shaped form which creates a loading spinner reminiscent of the Walmart logo.

This scene calls to mind the frustrating and often endless feeling of interacting with billing sites whether those be student loans, rent payments, or even your local big-box retail store. The frustration and stress referenced in this installation is palpable, not only from the two elements previously described but also by the overall chaos and density of the full installation. There is little room to breathe when viewing Garner’s scene but seemingly countless things that need to be seen. A large iPhone displays a phone call from “Student Loans”, there are pills, croissants, and iced coffees with bites taken out of them, and a notice sign reading “DO NOT FEED THE MILLENNIAL.”

My favorite part of the scene is the mailbox with four plush letters containing different ominous messages. One letter reads in part “Join our exciting UNPAID INTERNSHIP PROGRAM where you’ll.. Master the art of making coffee and PowerPoints… Get paid in experience, exposure, and maybe pizza” among other questionable opportunities.

Ash Garner

Ash Garner

Another “letter” is a notice of account overdraft from “DebtLife Credit Union” It reads: “While we understand that life is expensive, we are pleased to remind you that your hardship is our business model.” This strain of sardonic criticism characterizes Garner’s installation, oscillating between moments of playfulness and sharper, more biting gestures.

Ultimately, Soft Flesh, Volatile Insides is another strong show by Liz Faust, one of Baltimore’s most active and discerning curators. Having joined Goucher full-time just last year, Faust hit the ground running. She is no stranger to the gallery scene, with prior experience at Catalyst Contemporary and recent curatorial work at Goucher, Bogus Gallery, and Maryland Art Place, among others. The eye—and labor—of the curator is vital to any flourishing art ecosystem, and Faust’s contributions continue to shape Baltimore’s cultural landscape in meaningful ways.

While health and the body have always been political, this exhibition feels especially resonant amid the United States’ withdrawal from the World Health Organization and renewed attacks on the Affordable Care Act. In this context, Soft Flesh, Volatile Insides foregrounds the urgency of staying attuned to the body—not as an abstract site of representation, but as a lived, vulnerable system shaped by larger social and political forces.